Exploring the Parallels Between Weaving and Music

Throughout history, the relationship between weaving and music has taken on diverse forms. In the 19th century, the invention of the player piano was influenced by the Jacquard loom's perforated cardboard, while today's widespread use of the MIDI interface finds its origins in player pianos. Concepts of repetition, seen in modern Minimalism and classical fugues, mirror the repetitive nature of weaving. The significance of patterns resonates in both modern music history and weaving traditions, and shared terminology such as texture, color, rhythm, numbers, and time further intertwine these creative domains.

Early History: The Jacquard Loom and Piano Roll

A player piano, also known as a pianola, is an automated piano that utilizes programmed music stored on perforated paper or metallic rolls to operate the piano. A piano roll serves as a musical storage medium employed for the operation of a player piano.

In an archived article “Rubenstein on A Roll: It’s a Player Piano” from The New York Times (1), authored by Carolyn Darrow in 1982, he wrote: “In 1802, Joseph Marie Jacquard created the principle of the perforated cardboard used in the Jacquard loom, which revolutionized the weaving industry. Forty years later, another Frenchman, M. Seytre used this principle in the invention of the mechanically played pianoforte.”

In 1802, the French weaver Joseph Marie Jacquard invented an automated loom that could produce more intricate textile patterns using perforated punched cardboard tied together in sequence. Weavers initially translated their designed patterns onto perforated cards, which were then linked together in order. This allowed the loom to weave more complex patterns that were drawn on paper, all with reduced manual labor.

The invention of the perforated cards for looms had an impact on the development of player piano. Patented in 1842 by the French inventor Claude-Felix Seytre, the player piano can be seen as a musical adaptation of the Jacquard loom, and both the pianola with its perforated paper rolls and the Jacquard loom were early connections between art and technology. They made music and weaving more widely accessible and understandable to broader audiences. Between 1910 and 1930, player pianos were arguably one of the most significant components of the American music industry. During that time, radio, television, and films were not yet widespread, so if people wanted to listen to music, they either had to perform it themselves or rely on automatic musical instruments to play it for them.

Jacquard Loom (left) and ‘Player Piano’ by Arthur Reblitz (right)

Credit: National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution

Weaving's influence on music is evident in today's music technology. MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface), a technology which is used to store and recreate a composition or performance is a direct descendant of the paper roll in player piano. The piano roll is almost used in every DAW (Digital Audio Workstation), it's basically the main interface you use to control MIDI in your tracks. This innovation has provided unprecedented convenience for music production, making music composing/ creating for different instruments no longer exclusive to the upper classes.

Player piano roll (left) and modern digital piano roll (right)

Repetition in Weaving and Classical Music

Repetition is a fundamental characteristic of all kinds of music, and an explicit and essential component of Minimalism and fugues. In the context of Minimalism, composers often create concise musical phrases or motifs, progressively reintroducing them throughout a composition. Leopoldo Gómez wrote "By using repetition and track, minimalist works can create a sense of momentum and drive, as well as a sense of progression and development" in the essay "Minimalism in Music: The Power of Repetition and Track" (2). The images below provide a comparison between the musical score of Steve Reich's iconic minimalist composition "Piano Phase" and the tangible repetition and patterns found in woven fabric.

Score of the Piano Phase by Steve Reich (left) and a woven fabric (right)

Caption: The comparison between the score and woven fabric underscores the idea that both music and weaving are built upon the careful arrangement of repeated elements.

In medieval fugues, a central musical theme is established through the repetition of melody, creating harmonies and structures that highlight the interplay between repetition and variation. By weaving various melodic lines together, fugues craft intricate tapestries of sound that showcase the complexity that arises from skillful repetition and transformation.

In the broader context of music creation, repetition of some kind is universal, and when deliberately used, can be very impactful. As Elizabeth Margulis, the author of "On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind” (3), adeptly illustrates: "Repetitiveness actually gives rise to the kind of listening that we think of as musical. It carves out a familiar, rewarding path in our minds, allowing us at once to anticipate and participate in each phrase as we listen."

Similarly, in weaving, repetition plays a significant role. In other words, weaving is inherently a manifestation of repetition.

In textile production, the journey from preparation to the final woven product involves repetition across structure, visual aspects, and motion. The structure in textiles can be defined by the interactions of warp and weft threads as they pass over and under each other. Warp thread refers to the vertical thread on the loom to maintain tension when weaving cloth, and the weft thread is the thread that weaves the pattern and structure between the warp threads.. This requires repeating the process of interlacing the threads in a predetermined sequence. Different structures lead to the creation of distinct textures and patterns, often revealing repeated elements resembling dots upon close inspection. Additionally, in the design of patterns, there might be a need to repeat specific colors and motifs during the weaving process to generate specific visual effects.

As an example of repetition in motion, let's consider the process of using a floor loom. The creation of the warp involves repetitively winding threads onto a warping board to achieve the desired length. During the setup of the loom, each thread must be passed from the roller located at the back of a loom (the back beam) through the wire or cord with an eye in the center (called the heddle) in a particular order, and then threaded through the frame with vertical slits used to separate the warp threads (called thereed), ultimately connecting to the front beam. Since there are usually hundreds of warp threads to handle, this action must be repeated numerous times, the exact count depending on the desired width of the fabric. While weaving, the shuttle containing the weft thread traverses back and forth in rhythm with the foot pedals. Thus, it can be said that from the perspectives of structure, design, and technique, the essence of weaving is rooted in repetition and rhythm.

Basic parts of a loom (4)

For weaving artist Lenore Tawney, the interpretation of repetition is intertwined with her exploration of spirituality and the meditative aspects of weaving. She employed repetition to evoke a sense of ritual and contemplation, inviting viewers to experience timelessness and introspection in her intricate artworks.

Lenore Tawney, Untitled, 1978, Canvas, linen, and acrylic

Caption: Tawney used repetition to evoke ritual and contemplation, inviting viewers to journey into timelessness through her intricate artworks.

Patterns in Weaving and Music

The concept of patterns takes on various forms within the realm of music. For instance, in paper strip music boxes, the holes punched into the paper roll create musical scores that result in visual patterns on the paper, which are then directly translated into sound by the music box. In the musical context, a melodic pattern (5), is a fundamental unit which forms the basis of repetitive structures. In the context of minimalism, more complex musical patterns often emerge from variations of a simple structure.

Graphic score, also known as graphic notation, is a novel approach that composers began developing in the 1950s to visually represent music. In Michal Libera's essay "Paper scores of Music for Tape" from the book Ultra Hands, the Sonic Art of Polish Radio Experimental Studio, he noted that a score can effectively depict sound qualities as precisely as traditional staff notation. Graphic scores provide an alternative method of writing music, appearing markedly different from conventional musical notations. Composers employ various images and symbols to convey instructions to performers, enabling them to interpret the piece in a non-linear fashion. This approach transforms sheet music into a form which allows greater expression and fosters a greater connection between composers and performers.

Stockhausen: Elektronische Studie II (1954)

In composer David Bruce's video essay "Music Vs. Pattern” (6), he highlights that visualizing music enhances our perception of patterns. For instance, in the contemporary use of digital audio workstations for music production, patterns become evident as we observe the repeating structures and the repetition of individual notes in MIDI tracks. Musician Stephan Malinowski was a pioneer in developing computer software to transform the pitches played by instruments into animated patterns. Within the Visual music movement, the visual patterns we perceive precisely mirror the auditory patterns we hear. This interplay between sound and sight offers a deeper understanding of the intricate patterns woven into the fabric of music.

Steve Reich: Music for 18 musicians

Cover art: A woven fabric by Beryl Korot

Caption: Steve Reich's choice of a woven work as the cover for "Music for 18 Musicians" highlights his recognition of the inherent parallels between music and weaving. Just as his composition weaves together intricate musical patterns and layers, the woven artwork visually represents the interplay of threads and colors, mirroring the complex harmonies and textures present in the music.

In weaving, a pattern refers to the repeated design or arrangement of threads that creates a distinct visual motif or structure in the fabric being woven. It involves the deliberate arrangement of warp (vertical) and weft (horizontal) threads to produce a specific design or texture in the woven material. Patterns can vary widely, ranging from simple geometric shapes to intricate motifs, and they play a significant role in determining the overall appearance and character of the woven fabric.

Anni Albers was one of the most influential textile artists of the 20th century. She is known for discussing and experimenting with patterns in weaving in both academic and experimental ways. She explored the interplay of colors, textures, and geometric designs in her woven artworks. Her writings and teachings, particularly her book On Weaving, delve into the technical and artistic aspects of weaving, including the intricate patterns that can be achieved through different weaving techniques. Albers' work and contributions have had a significant impact on the understanding and advancement of patterns in the realm of weaving.

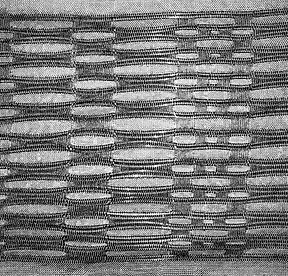

Detail of Anni Albers, “Intersecting,” 1962, cotton and rayon

Shared Principles Between Weaving and Music

Within the domain of music, Musique Concrète was developed by French composer Pierre Schaeffer beginning in the early 1940s. Musique Concrète explores various qualities within music, such as sound texture, timbre, rhythm, duration, pitch, and intensity. Similarly, during the Bauhaus period, weaving primarily explored the qualities of texture, color, pattern, and the integration of art and furniture, combining traditional weaving techniques with modern design principles to create innovative and functional textile works. Both music and weaving have their own principles. Basic principles in music include timbre (color tone), rhythm, duration (time), and intensity, while in weaving, principles encompass color, rhythm, intensity, and time.

In a thesis called "Woven Music" (7) in 2003, the author Melanie Jackson explored shared elements and principles between weaving and music.

Within the domain of music, the concept of tone color, also referred to as timbre, pertains to the unique sound quality of an instrument or a combination of instruments. For instance, violins are often described as having a "bright" sound, while cellos may be characterized as "warm" or "mellow." In weaving, the concept of color is more commonly discussed in relation to substances like dyes and pigments.

In the context of weaving, a fabric’s texture also captures the visual appearance of fabric, which emerges from the weaving arrangement of its warp and weft threads. Texture encompasses qualities such as roughness, smoothness, itchiness, silkiness, prickliness, and softness. However, in music, texture mainly denotes the impact of different layers of sound and melodic lines within a composition, along with their relationships. This term originated in the field of textiles, symbolizing the intricate interlacing of various threads—whether loosely or tightly, uniformly or in diverse combinations.

Additionally, time's significance in weaving is often more pronounced during the preparation stage than in the actual weaving process. In music, time, or tempo, pertains to the numerical indications on the staff at the start of a piece, signifying the meter or time signature.

Furthermore, rhythm holds significance in both weaving and music as a foundational element. In weaving, rhythmic motions of thread interlacing create fabric structure and patterns, while musical rhythm organizes sound over time, shaping beats, meter, and flow.

In the exploration of the intertwining parallels between music and weaving, it is worth considering the implications of these similarities for our understanding of the music and weaving industries today, as well as their broader significance. Music and weaving are interrelated/connected/have shared history, from the influence of the Jacquard loom's invention on piano rolls in the 19th century and its influence on the development of MIDI technology, to the concept and use of repetition in classical music, and the pattern in the visual music movement and electronic music since the 20th century, along with the shared principles between music and textiles. The threads of history, repetition, patterns, and principles continue to be woven into a new tapestry with endless possibilities and beauty for us to explore.

Special thanks to Evan Korte and Elliot Korte for editing the essay.

Footnotes and links:

(1) ANTIQUES; RUBENSTEIN ON A ROLL: IT'S A PLAYER PIANO

(2) Minimalism in Music The Power of Repetition and Track: Exploring the Art of Minimalism in Music

(3) Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis

(4) Basic Parts of a Weaving Loom and Their Functions

(5) Melodic pattern

(7) Woven Music

MIDI History:Chapter 2-Player Pianos 1850-1930

https://www.midi.org/midi/midi-articles/midi-and-player-pianos

Stuck on repeat: why we love repetition in music

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/apr/29/why-we-love-repetition-in-music-tom-service

Music for Contemplation: History and Evolution of the Minimalism Genre

https://www.soundoflife.com/blogs/experiences/music-minimalism-genre

Ultra Sounds. The Sonic Art of Polish Radio Experimental Studio

https://msl.org.pl/ultra-sounds-the-sonic-art-of-polish-radio-experimental-studio-1/